Former Moss Bluff fire chief recalls 1982 blaze that destroyed Sam Houston High

Published 9:25 am Sunday, January 9, 2022

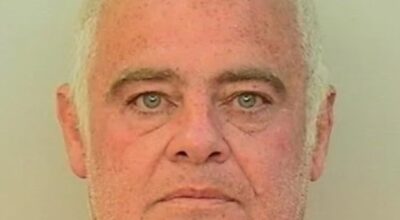

- Firefighters battle a fire at Sam Houston High School Jan. 11, 2982, in 18-degree weather. (Special to the American Press)

Former Moss Bluff Fire Department Chief Michael Kuk can still remember the smell of burning tar as he watched the roof of Sam Houston High School melt before his eyes.

“It’s hard to believe it’s been 40 years,” he said while scanning through a scrapbook of 35mm four-by-six prints of the Jan. 11, 1982, fire. “That day I was supposed to have a surprise party for my 33rd birthday. I had begun suspecting something because firefighters from the overnight shift were still hanging around and everyone was in a festive mood at the station.”

The mood didn’t last long.

“It was the coldest day of the year, only 18 degrees,” Kuk said. “The water works district superintendent had come to the fire station that morning and said, ‘Chief, if there are any fires today and they’re bad your people need to call me because I’ll have to shut valves to make sure you have enough water to fight it.’ ”

Moss Bluff at the time had only one water tank and that day it was half-full.

The superintendent gave Kuk his home phone number — “cell phones weren’t invented at the time,” he said — and bid him good day.

Kuk said the Sam Houston Jones Parkway station — which continues to serve as the main fire station in Moss Bluff — had a shell rock surface driveway at the time that lead up to the building.

“You could hear the shuffling of the shell everywhere when someone drove up and my captain heard the sound that morning — it was about 11:30 a.m. at that point — and so I came out of my office and they told me, ‘We’ll go get the medical gear while you go see what the emergency is.’ So here comes this woman at the door, all out of breath, and she said, ‘My God, y’all, do you know the high school is on fire?’ ”

He when said he stepped outside, he could see the smoke a block away.

“Twenty-four out of our 25-person staff came, everybody showed up,” he said. “Three minutes into the fire, I called mutual aid. I had to. They came as far as Jennings to help us. We had no water. There was one hydrant in front of the school and two more about 2,000 feet away in opposite directions. Lake Charles hooked on to the eastern one and Sulphur hooked on to the far west one to bring more water to fight the fire. We didn’t even have enough water to control the pitch of the fire.”

The school was L-shaped with a main entrance, library, principal’s office, secretary’s office, band room, classrooms and a science lab.

“The roof was flat and it was a big wide-open air space,” he said. “Everything was wood — a wood-sided school, wood framed and the roof was actually pea and gravel, basically small rock on tar. The heat was unreal.”

He said his team tried to create what is called a trench cut, in which firefighters cut a 3-by-5-foot wide trench in hopes when flames approach, a natural ventilation would fight the fire with what little water stream they had.

It didn’t work.

“Every time we got on the roof, it was too dangerous,” he said. “It was spongy and little pockets of flame would pop up through the hot tar. I called them little fire devils.”

Kuk, who had been fire chief for seven years at that point, said he couldn’t risk having his team climb up there.

Ultimately the firefighters were unable to stop the fire because they ran out of water at about 4:30 p.m., Kuk said.

“If we would have had the water we could have literally deluged the school with water with two 500-gallon deck guns. They’re big water guns and it could have stopped it. We were lucky to get 300 gallons a minute.”

He said they were able to intersect hose steams to save the offices, which in turn preserved all the school records.

“That was a big accomplishment because databases back then didn’t exist.”

Kuk said the fire was so hot and so large that pine straw from a wooded area behind the school caught fire and burned the jackets surrounding the team’s fire hoses.

“Firefighters had to turn around and put out the fires on the hoses so they could keep going,” he said. “It was pretty crazy. It was bitter cold that day and nobody was used to being outside that long in 18-degree weather, but no one took a break that day.”

After the team got the fire under control, they formed a watch line 24 hours a day for five days, letting the school’s ruins burn themselves out.

“We put water where we could, but what a shame.”

He said the state fire marshal’s office investigation took 30 days, and the results were shocking.

“The state fire marshal’s office found that every Bunsen burner — there were 16 or 18 of them — in the chemistry lab was turned in the on position,” Kuk said. “By having all that natural gas in the building, it was a blow torch.”

He said it’s a miracle no one was injured that day.

“It was a school day, but classes had been canceled because it was too cold in the classroom for the students.”

Kuk said one memory that sticks out from the fire is the line of students who gathered outside the school as the flames burned.

“They just stood there in a line, crying,” he said. “Their school was burning. It was very emotional for them.”

Kuk said he plays keyboards in a few Cajun bands in the area — his stage name is “Chief of the Keyboards” — and even 40 years later he continues to bump into people when he’s out performing who bring up the school fire.

“One thing good that came out of that fire was that it gave a lot of muscle to the water works district to where their board kind of woke up and realized they needed to put in more fire hydrants, especially with the booming of the community,” he said. “Then the Police Jury adopted an ordinance that all new subdivisions would have fire hydrants no less than 1,000 feet apart. It’s nice that something good came out of something so horrible.”