Jim Beam column:Polio story has ties to virus

Published 7:32 am Thursday, December 16, 2021

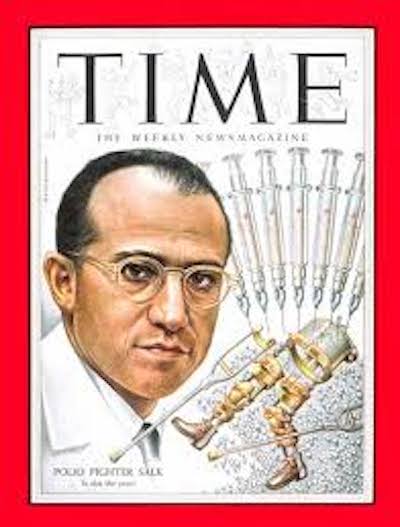

- Dr. Jonas Salk, who developed the polio vaccine, made the cover of Time magazine on March 29, 1954. "Is this the year" was on the cover.time.com

Charlie Beam, my dad, had polio when he was six and ended up with only one good leg. He had to walk with a crutch for the rest of his life. Since he could still do almost anything, including drive a car, my four siblings and I and almost everyone else never actually considered him to be handicapped.

I mention this after running across a story from March 25, 2020, titled, “The deadly polio epidemic and why it matters for coronavirus.” The story is by Carl Kurlander, senior lecturer at the University of Pittsburgh, and it appeared in The Conversation, a nonprofit, independent news organization.

Kurlander said, “Like a horror movie, throughout the first half of the 20th Century, the polio virus arrived each summer, striking without warning. No one knew how polio was transmitted or what caused it … There was no known cure.”

Swimming pools and movie theaters were closed during polio season and parents stopped sending their children to playgrounds. Kurlander said kids, who seemed targeted by the disease, were taken from their families and isolated in sanitariums.

The number of polio cases peaked in the U.S. at 57,879 in 1952, resulting in 3,145 deaths. Those who survived the highly infectious disease could end up with some form of paralysis, forcing them to use crutches and wheelchairs, or be put into an iron lung to help them breathe.

Polio was ultimately conquered in 1955 by a vaccine developed by Jonas Salk and his team at the University of Pittsburgh.

Kurlander said he produced a documentary in conjunction with the 50th anniversary celebration of the polio vaccine titled, “The Shot Felt ‘Round the World.” He said it told the stories of the many people who worked alongside Salk in the lab and participated in vaccine trials.

“I believe these stories provide hope in the fight to combat another unseen enemy, the coronavirus,” Kurlander said at the time the deadly virus surfaced in this country.

Before the vaccine, polio caused more than 15,000 cases of paralysis a year in the U.S. and was called the most feared disease of the 20th Century.

Kurlander said with the success of the polio vaccine, Jonas Salk, 39, became one of the most celebrated scientists in the world. He refused a patent for his work, saying the vaccine belonged to the people. Leading drug manufacturers made the vaccine available, and more than 400 million doses were distributed between 1955 and 1962, reducing the cases of polio by 90 percent. Kurlander said polio became a faint memory by the end of the century.

President Franklin D. Roosevelt kept his own paralysis from polio hidden from the public, but he organized the nonprofit National Institute of Infant Paralysis, later known as the March of Dimes. Roosevelt encouraged every American to send dimes to the White House to support treating polio victims and researching a cure.

Dr. Peter Salk, Salk’s eldest son, said that was a time when the public trusted the medical community and believed in each other. Kurlander said that was an idea that needed to be resurrected when the coronavirus surfaced.

The next part of the story could not have taken place in today’s political climate. Kurlander said Salk in 1953 was given permission to test the vaccine on healthy children and began with his three sons, followed by a vaccination pilot study of 7,500 children in Pittsburgh schools.

While the results were positive, the vaccine still needed to be tested more widely to gain approval. The March of Dimes in 1954 organized a national field trial of 1.8 million schoolchildren, the largest medical study in history.

The study data was processed and on April 12, 1955, six years from when Salk began his research, the Salk vaccine was declared “safe and effective.” Kurlander said church bells rang and newspapers across the world claimed “Victory Over Polio.”

Kurlander said March 2020 was a frightening time in this country when the coronavirus spread in ways reminiscent of polio. He said it was instructive to remember what it took to nearly eradicate polio and what we could do when we work together to face a common enemy.

Unfortunately, many Americans no longer trust the medical community and the coronavirus, our common enemy, has claimed over 800,000 lives in this country. We are as far away from working together today as when the virus came calling nearly two years ago.